The AutoML Benchmark

This blogpost is about why we set out to write our paper “AMLB: an AutoML Benchmark” (📄paper, 🤖code) and provides a brief overview of its main contributions. In the end, we will share how you can make an impact on the future of this benchmark and automated machine learning (AutoML). But before we get started, here’s the tl;dr in haiku form:

research driven by

experimental results

we need a benchmark

Why do we need a standardized benchmark?

We started the project back in 2018. Over the summer, I (Pieter Gijsbers) got together with Erin LeDell and Janek Thomas to work on three problems we had identified:

- in the field of automated machine learning (in 2018), different papers would rarely evaluate their methods on the same data, and

- researchers would often make simple “user errors” when evaluating methods proposed by others, and

- the analyses were almost exclusively focused on predictive performance.

We decided to address these problems by introducing a benchmark suite, benchmark software, and a multi-dimensional analysis. That initially culminated into an introductory paper at the AutoML Workshop at ICML 2019, and ultimately in our publication at the Journal of Machine Learning Research. Let’s have a closer look at why these problems needed solving and our resulting contributions.

The Benchmark Suite

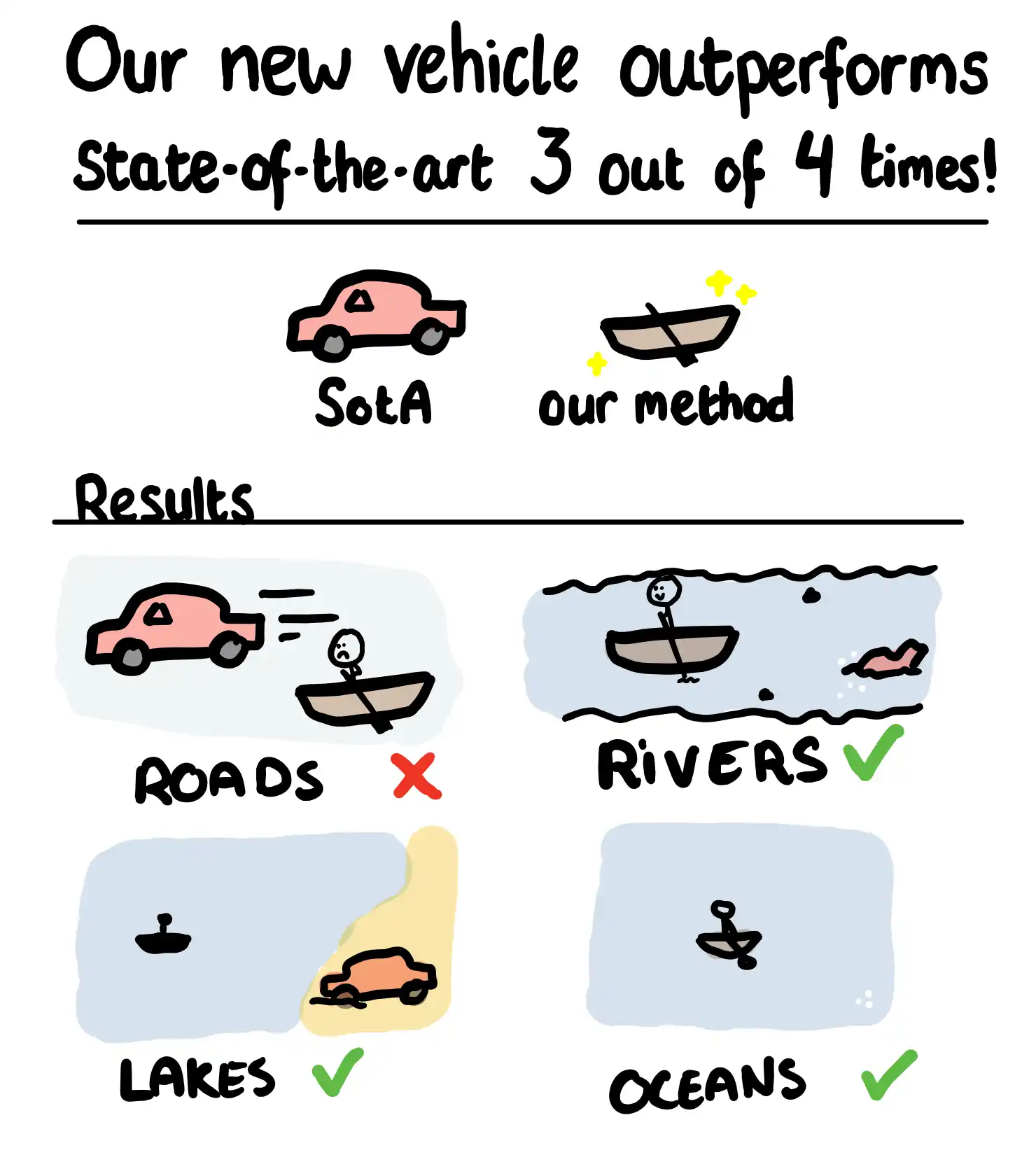

Research papers evaluating their methods using different sets of data inadvertently means that results are not comparable across different papers. This makes it impossible to determine state-of-the-art or to track progress in the field overtime. It may also lead to accidentally reporting optimistic results. For example, when researchers use a dataset both during development and evaluation, design decisions are made during development which improve performance for that dataset, but it is unlikely that it improves performance for unseen datasets equally. Thus, performance on that dataset is likely optimistic (i.e., better) compared to what you would expect on unseen datasets.

Even if datasets used in evaluation are not used during development, the researchers’ bias on which type of data they find important, such as biomedical data or big data, may lead to a similar “accidental cherry picking”. That type of data is reasonably assumed to be present during both development and evaluation, and other types of data for which the methods were not developed may be absent also in evaluation. This means that areas where methods may have blind spots are not evaluated and not reported on, giving an incomplete picture of the method’s strengths and weaknesses.

Having a curated set of datasets for evaluation managed by the community and carefully chosen to represent various data domains and characteristics should alleviate these problems. That is why we propose the initial version of such a standardized benchmark suite. The benchmarking suite contains 71 classification and 33 regression datasets that come from many different domains and exhibit many different dataset characteristics. We hope that with a benchmarking suite of this size and variety, we can trust in the generalizability of the results obtained.

The Benchmark Software

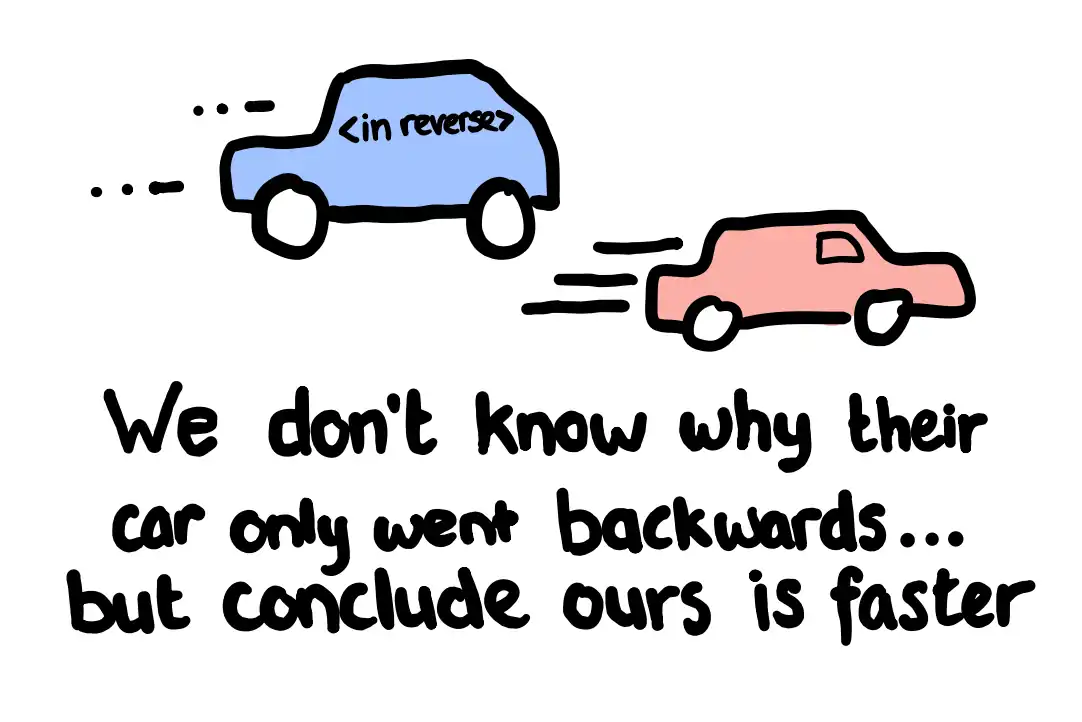

Another consequence of using a different set of data for each paper is that researchers need to evaluate the methods of others on their data. There are multiple examples where a method’s performance reported in papers are, for lack of a better word, the result of misunderstandings (or “user errors”). For example, a paper introducing method \(X\) and comparing it against state-of-the-art framework \(Y\) would report a failure of framework \(Y\) on dataset \(D\). In several cases we could diagnose the problem that caused the failure of framework \(Y\) on dataset \(D\) directly from the paper or a few minutes of inspecting the code. Examples would include using an out-of-date release or a wrong configuration of framework \(Y\).

Luckily, as computer scientists, we have a wonderful tool in our belt to reduce human error: automation. That’s why we built standardized benchmarking software complete with developer-friendly AutoML framework integrations.

With the paper we released our open source benchmarking software. It allows you to run an AutoML evaluation with a single command. A simple python runbenchmark.py autosklearn openml/s/271 1h8c is all you need to evaluate autosklearn on our entire classification benchmark (OpenML suite 271). The software takes care of installing autosklearn, (down)loading the data and providing it to autosklearn, configuring autosklearn with a 1 hour time constraints with a limit of 8 CPU cores (hence 1h8c), monitoring its progress, and processing the predictions of the final model.

This level of automation means that no one is accidentally training on a test set. No one accidentally uses different parallelization for different AutoML frameworks, and no one accidentally optimizes for the wrong metrics. It’s a great step forward for fair comparisons. At least, that’s the idea. In many cases we make good on the promise, but we are working with a moving target (new framework releases) and bugs happen (see “The Future” below).

The way we achieve this is by collaborating with AutoML framework developers. We built a strong shared framework that takes care of bootstrapping the experimental setup. It has generic functionalities for (down)loading data, installing dependencies, keeping track of experiments, processing results, and so on. Then, for each framework we have a minimal integration module which requires an installation script and a Python script which takes as input the data and task description and is expected to produce predictions as output. These integration scripts are often developed by, or in collaboration with, the authors of the AutoML frameworks which significantly reduces the chance that frameworks are used or configured incorrectly.

A Multi-Dimensional Analysis

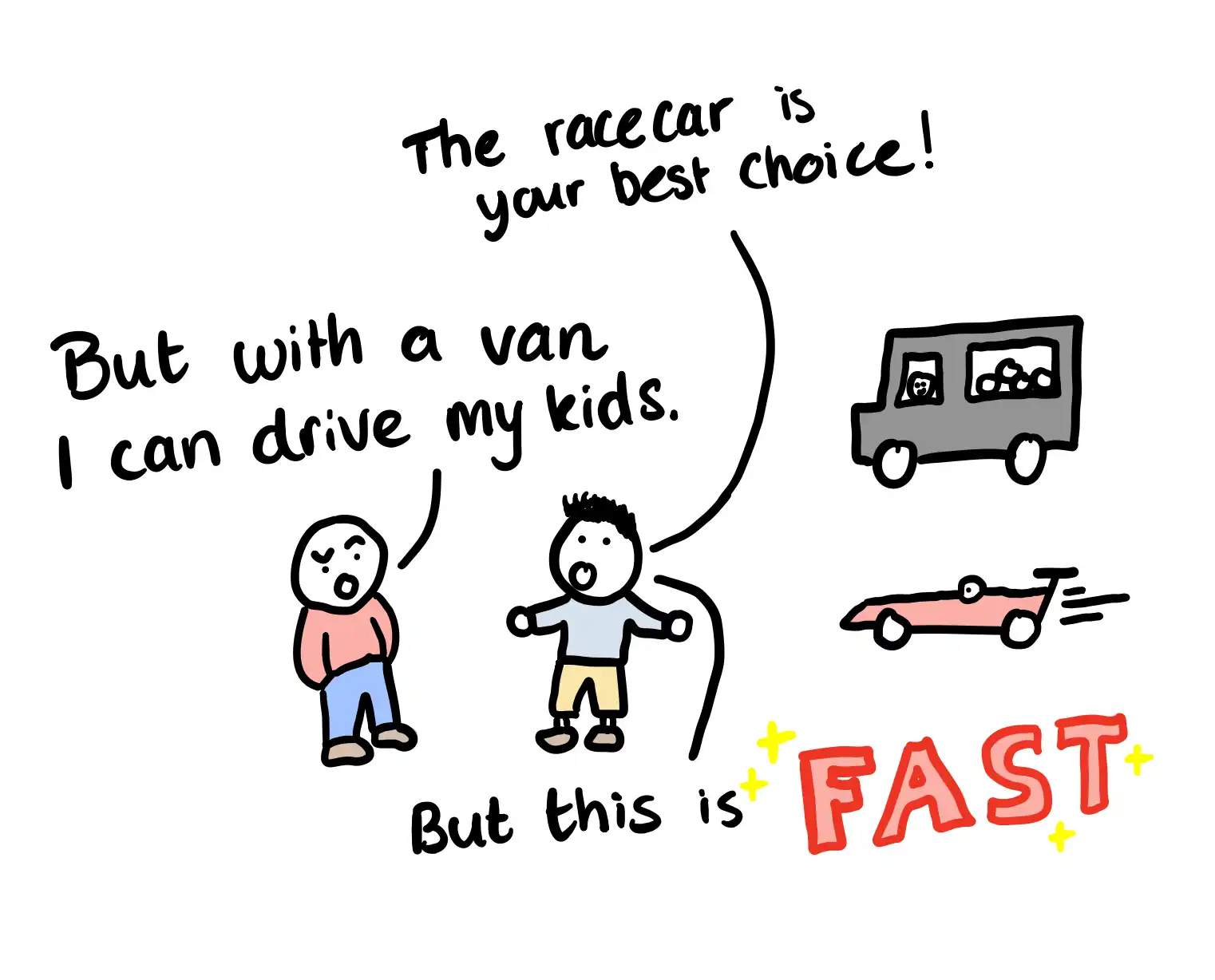

The last problem we identified was a single-minded analysis of the results. AutoML frameworks were compared (almost) exclusively on predictive performance. While this is a very important aspect of the final model, it provides an incomplete picture. Depending on the application that the model is trained for, other aspects like fast inference time or interpretability may be important or even required. In those cases, being able to assess the trade-off between predictive performance and other model dimensions is crucial. The characteristics of the AutoML framework itself may also be important: is it robust? is it configurable? does it adhere to resource constraints? That’s why we advocate for a multi-dimensional analysis of the results.

In our paper we evaluate 9 AutoML frameworks on our benchmarking suite and analyze the results. When analyzing predictive performance, we answer questions like: Which framework ranks best? Is it significant? How does that translate to absolute and relative differences? Do results hold across all data characteristics, or do we see some AutoML frameworks which work particularly well on datasets with certain characteristics?

But we also look beyond predictive accuracy. We inspect the learned models’ inference time, and discuss its trade-off with predictive performance. We also investigate when AutoML frameworks fail and why: Is it triggered by the data? Is it misuse of resources? Do they adhere to the given time constraints?

The experiments in the paper are from 2023, so results would indubitably be different for frameworks today. Bugs are fixed, better methods for building better models are developed. However, we hope the paper serves as an inspiration and example for providing a more thorough multi-dimensional analysis.

Challenges and Limitations

For more background, examples, challenges, and references you will want to have a look at the paper. It presents ideas presented here in more depth but also includes additional information on e.g., limitations of the benchmark, and it also contains the results and analysis of 9 frameworks on 104 datasets!

The Future

Overtime the landscape of data problems changes, as do the capabilities of AutoML frameworks, and the benchmarking suite should be updated to reflect that. One glaring ommission in the benchmark (in my personal opinion) is the lack of text data. In the original benchmarking suite presented in the paper, all datasets have strictly numerical or categorical data. This is for historical reasons, as a significant number of the AutoML frameworks in 2018 did not handle text data natively. But text data is ubiquitous, modern AutoML frameworks are well-equipped to deal with it, so it’s time we reflect that in the benchmark.

Moreover, there is nothing uniquely “AutoML” about the AutoML benchmark. It benchmarks anything for which you write an integration script that takes as input a task and constraint description, and provides predictions as output. Sure, many algorithms may not deal with various dataset characteristics out-of-the-box (e.g., text data may need to be encoded) and the method may not adhere to time constraints, but that doesn’t mean the software can provide much of the same benefits of automation to evaluating “regular” ML algorithms (in fact, TabRepo used AMLB). We hope to explore this further and potentially position AMLB for more general tabular ML benchmarking.

And last but not least, though perhaps not as sexy, is the brunt of software engineering work. As time goes on, AutoML frameworks have new releases, people use different hardware, and AutoML is used for new problems, which means we are always working with a moving target. The benchmarking software needs to be maintained to work with modern stacks, extended to allow evaluation of different problem types, and incidental bugs need to be squashed. On top of that, we are continuously exploring ways to make the software easier to use for both developers and researchers.

The benchmark isn’t perfect, or even finished. It’s a start. And we invite you to collaborate with us.

There are many ways to contribute. The easiest way is to help is to leave a ⭐️ on our GitHub project, talk about the AutoML benchmark, and use it in your work. There are also a number of no-code contributions that help us out greatly:

🤝 Help people on our GitHub issue tracker

📚 Improve our documentation

🤓 Identify interesting new datasets

And finally, we very much welcome code contributions. 🧑💻

This post was written by Pieter Gijsbers and need not reflect the view of co-authors.